Did you know that there’s a cycle path that follows the full length of the Berlin Wall? The most dramatic part of the Wall surely was the 40 km inner-city section that divided West and East Berlin. But a much longer stretch, 125 km long, ran around the whole of West Berlin, separating it from the surrounding GDR countryside. Apart from keeping GDR citizens from entering West Berlin, it also caused a kind of claustrophobia in many West-Berliners, who could not easily leave the city. You can try to get some idea of what life was like outside and inside the Wall by taking the Berliner Mauerweg, or Wall Trail, a fully signposted cycle and hiking path that follows the course of where the wall used to be – all 165 kilometres of it.

I cycled the path in two days in September 2015, starting at the former Chausseestrasse border crossing, continuing south through the city, and following the trace of the Wall clockwise. On the first day I cycled 72 km to Potsdam-Griebnitzsee, and took the S-Bahn back to Berlin-Mitte. On the second day, from the same S-Bahn station I continued clockwise for another 95 km back to Mitte.

East and West

Cycling the Wall 25 years after German reunification is a strange experience. First of all, it’s astonishing how little there is left of it. There are information panels on the path that show aerial photos of what the border strip looked like in the 1980s – sandy wasteland, watchtowers, outer wall, inner wall… almost all of this has gone. On 125 km of Mauerweg outside the city, I’ve spotted two remaining watchtowers, and a few slabs of inner and outer wall – that’s it. (If you’re looking for that kind of thing, you might as well stick to the inner city). The no man’s land of the death strip is either overgrown, built up, or otherwise disguised. Again, there’s only a few places where it is immediately recognisable.

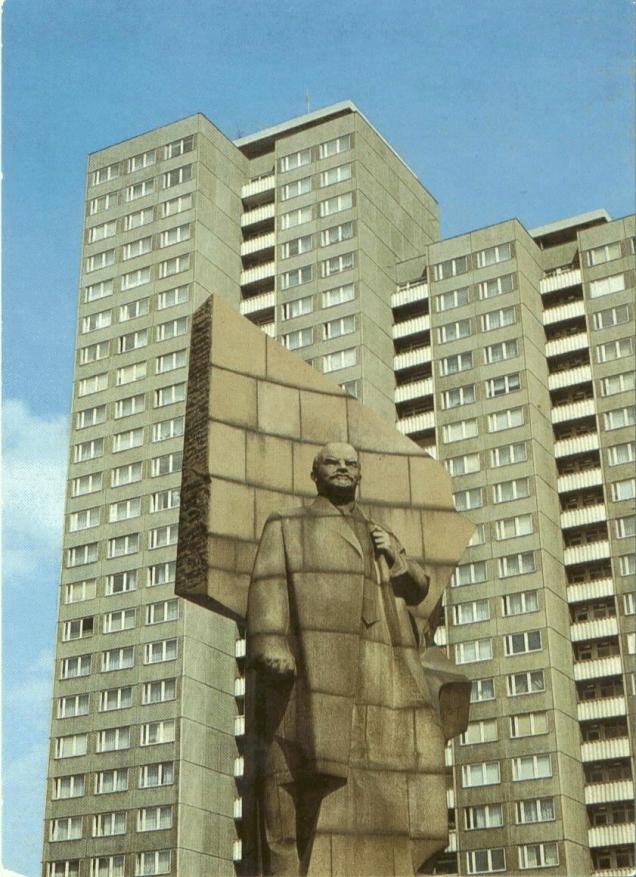

What’s also strange is how hard it has become here to tell East from West. If you’ve been to Brandenburg towns outside Berlin (Oranienburg, for example), you probably agree that they still look very “GDR” in places. But on my clockwise run down the path that straddles the West-Berlin border, I had to keep reminding myself that “left is East” and “right is West”. The bits that run through nature of course look neutral. And in the parts where you ride through built-up areas, the houses on the eastern side are often just as nice (often because they’re newer) as the ones in the former West.

Cherrypicking or the Full Monty?

Obviously, doing the full Wall ride is satisfying in itself. The trouble is that if you want to do it justice, and also take some time for photography or reading the many explanatory signs, you’ll need three, maybe four, rather than just two days.

So if you have limited time, or are not keen on two full days of cycling, or want to experience more of what you see en-route, I would recommend cherry picking some stretches. Here’s the two that I liked best: one is the inner city bit that many guided tours also follow (partially or fully): starting at Bornholmer Strasse crossing in Prenzlauer Berg, the first border crossing to open on the night of 9 November 1989, and continuing as far south as, let’s say, Treptower Park.

As for the country part of the Mauerweg, my favorite part starts at Potsdam Griebnitzsee S-Bahn station, which is right on the Wall Trail, and can easily be reached from Mitte on S7 and S1. There’s a bike (and canoe!) rental place right at the station. Continue northward, and you’ll cross Glienicker Brücke (famous for its Cold War spy exchanges), and ride through the park of Cecilienhof Palace. It’s a great way to explore the UNESCO Potsdam Havel area. The path traces the Havel lakes, past the lovely Heilandskirche (Church of the Redeemer), and then there’s a long forest ride. The first opportunity to put you and your bike back on a train to Mitte is at Berlin-Staaken railway station. The distance is roughly 35 km. Or you could turn around at the church and make your way back to the bike rental place at Griebnitzsee.

What bike?

Some people say you need a mountainbike to ride the Mauerweg. That’s not strictly true, although if you have one, go for it. The thing is, the path is quite good (for a 165 km initiative), but not that good. The tarmac, for example, is broken by tree roots in many places which makes for a very choppy ride. There’s stretches of gravel, which I like, some sand, which is OK depending on recent weather and your tyres, and a few kilometers of cobble stones, which are terrible. All of these problems are ok for short distances but if you want to complete the loop they can get very tiresome.

The southern half is not very hilly, but I did about 400 metres of climbing on the northern section (mostly short, steep hills). So if you can get your hands on a bike that has front suspension (for the bumps) and gears (for the hills) that would be good. Unless you have the stamina of a Paris-Roubaix racer, road bikes (Rennrad in German) are not suitable, not to speak of fixies (but then, they’re not actually for riding, are they?) Obviously bring a tyre repair kit (Flickzeug, one of my favourite German words) as most of the time, it’s a heck of a long walk to the nearest S-Bahn station or bike shop.

Catering

Which brings us to food. My app says I used about 4000 calories for the whole ride (with a 20 km/h moving average, which is not that fast). That’s the equivalent of 40 bananas or 8 Big Macs, none of which you can buy on the trail. There are some shops and cafes here and there, but outside the city, there are many stretches where you can ride for 30-40 kms without getting to a food outlet. You could interrupt your ride and cycle into the city to find food, but it’s probably better to bring lots of fruit and sandwiches.

Navigation

To find my way around, I mainly just used the official signs. I also had a GPS on my handlebars, which was nice as a backup, and as a warning for upcoming turns. You can download my gps .gpx track here. A map is great for getting your bearings in the grander scale of things (the Mauerweg has so many twists and turns that it’s easy to get disoriented). The PublicPress map is cheap, durable, and, importantly, clearly shows S-Bahn stations, so you can always find your way back home. One side of the map shows the full Mauerweg, the other side shows an enlarged segment of the city centre. It’s also got some text explaining the sights along the way. Highly recommended.

So – the only thing left to do is actually do it. Stock up on food, pump up those tyres, and off you go. Just start riding, see how far you get (there’s plenty of S-Bahn stations in the first 20-30 kilometres to cut your ride short if you want to). There’s space in the comments for your experiences!